PopArt: a strategy to preserve works of art in plastic

POPART: Why such a project ?

During the twentieth century, artists used synthetic polymers to create important pieces that are recognized nowadays as masterpieces in our museums of modern and contemporary art. Unfortunately, some artefacts are deteriorating fast and their conservation constitutes a real challenge. This project has, among other things, allowed us to assess the "condition" of a number of collections. A survey carried out in London by the Victoria and Albert Museum and in the British Museum identified that among the 7,500 synthetic objects containing polymer more than 12% of them require urgent conservation measures. This number might be considered as a low figure, nevertheless it has to be realized that the survey only takes into account pieces in the final stage of the deterioration process, made visible by physical changes.

Nevertheless these works are recent and there are fears that the situation may worsen dramatically in the coming years.

Nevertheless these works are recent and there are fears that the situation may worsen dramatically in the coming years.

Actually, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the strategy to implement in order to limit the deterioration rate of this type of object. For this reason I set up the “POPART” project (acronym for Preservation Of Polymer ARTefacts). Its objective is to establish and validate an approach to better understand, preserve and maintain plastic objects found in museum collections. The project builds on the work of 12 research teams from eight European countries and the United States, as the Getty Conservation Institute was indeed involved in this work. Museums participated, enabling us to work in the field on collections, with art conservators and curators.

Can you provide a brief history of the polymers adopted by artists ?

Celluloid (cellulose nitrate) was the first semi-synthetic plastic material to be extensively used by artists in the early decades of the 20th century. The revolution in fine art was already well established by the breakthroughs of Cubism and by 1920’s artists like Naum Gabo. Other cellulose esters were subsequently used. In the 1930’s, Gabo and also his brother Antoine Pevsner and Marcel Duchamp worked with polymethyl methacrylate* (PMMA) because of its transparency and luminosity. Ten years later, artists like László Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Archipenko took advantage of this polymer, which was easy to cut, paste and polish and which, under the influence of heat, could give birth to innovative forms.

Celluloid (cellulose nitrate) was the first semi-synthetic plastic material to be extensively used by artists in the early decades of the 20th century. The revolution in fine art was already well established by the breakthroughs of Cubism and by 1920’s artists like Naum Gabo. Other cellulose esters were subsequently used. In the 1930’s, Gabo and also his brother Antoine Pevsner and Marcel Duchamp worked with polymethyl methacrylate* (PMMA) because of its transparency and luminosity. Ten years later, artists like László Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Archipenko took advantage of this polymer, which was easy to cut, paste and polish and which, under the influence of heat, could give birth to innovative forms.

In the 1960’s, Plexiglas became a common material! Indeed, it is found in the works of varied artists such as Wurmfeld, Judd, Kolig, Reimann, Beasley, Wesselmann, La Pietra, Marotta, Nevelson, etc.

* This polymer is principally known by its first trade name Plexiglas even if the leader in PMMA is Altuglas International of the Arkema Group under the brand name Altuglas®. It is also sold under other trademark names.

During that decade, artists like Gilardi, César or Chamberlain used polyurethanes, which were originally used for insulation. Another material widely used by artists is polyester. Available in liquid form, it can be cast or, in particular, used as a bonding agent between layers of fibre glass and thus allow mouldings to be constructed. Ideal for boat hulls, car kits and outdoor sculptures, the simplicity of this technology was acclaimed by Saint Phalle, Klasen, Jaco or the hyperreal Hanson.

The POPART project studies on the nature of modern art collections show that polyesters, PMMA, PVC are among the most commonly used but there are also older compounds such as Bakelite.

How do these plastics deteriorate and which ones are a priority to conserve ?

The causes of deterioration are multiple. They may have chemical origins – by the action of oxygen, light, heat and moisture – or mechanical, during handling. These deteriorations result in the appearance of deformations, distortions, shrinking, cracks, accretions (surface deposits), discoloration, texture changes, fading, etc.

The causes of deterioration are multiple. They may have chemical origins – by the action of oxygen, light, heat and moisture – or mechanical, during handling. These deteriorations result in the appearance of deformations, distortions, shrinking, cracks, accretions (surface deposits), discoloration, texture changes, fading, etc.

Over time, all plastics deteriorate but, for some, this deterioration occurs after only a few decades. Among the most ephemeral of them, which therefore require the most attention, are cellulose nitrate, cellulose acetate, polyvinyl chloride and polyurethane foams.

It should be noted however, that PMMA works which have benefited from correct conservation (including protection from UV) seem to have better resisted the ravages of time than those unprotected. They are nevertheless highly sensitive to abrasion.

It should be noted however, that PMMA works which have benefited from correct conservation (including protection from UV) seem to have better resisted the ravages of time than those unprotected. They are nevertheless highly sensitive to abrasion.

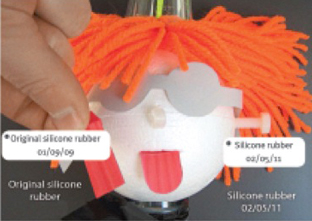

During this project we created a series of test objects made of eleven plastics that were exhibited in various museums and institutions. In less than two years, it was possible to follow the natural aging of these materials by spectroscopic methods but alterations were already clearly visible to the naked eye for the parts in polyurethane-ester foam.

What strategies and techniques have you implemented to protect the works of art ?

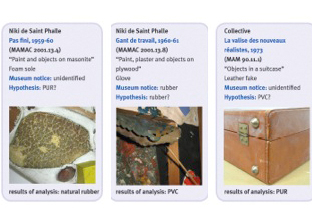

Prior to any decision regarding a collection, the main issues are to identify the different types of plastics in order to suggest correct treatment (e.g. one must know that some plastics are sensitive to water-based cleaning) and procedures for storage and exhibition.

Within the framework of POPART, we especially tested portable devices (infrared spectroscopy, near infrared or Raman, etc.) able to determine which polymers are components of a work without sampling. We have established databases of recent and aged polymers for analysis in near infrared; a partner company will market these databases.

Methods of analysis were developed and blind tests carried out by the teams. The many infrared spectra, mass spectra, etc. obtained will be made available to the scientific community.

Methods of analysis were developed and blind tests carried out by the teams. The many infrared spectra, mass spectra, etc. obtained will be made available to the scientific community.

After this first step, we focused on methodologies for assessing the level of alteration of objects by applying the latest imaging techniques: Terahertz, near infrared. Once again, being able to identify affected zones and quantify the level of deterioration represents a huge benefit for the conservation of objects and the definition of appropriate treatment.

What about the curative conservation of these objects ?

In terms of maintenance of these collections, we assessed the adequacy of cleaning with water based and organic solvents in order to measure their effectiveness and long-term effects on the appearance and stability of objects. A methodology to determine the appropriate treatment was proposed. Finally, we explored the processes of consolidation of objects made of polyurethane foam. Among the promising solutions, aminoalkylalkoxysilanes (AAAS) seem to offer a "last chance" treatment to reinforce dilapidated objects.

In terms of maintenance of these collections, we assessed the adequacy of cleaning with water based and organic solvents in order to measure their effectiveness and long-term effects on the appearance and stability of objects. A methodology to determine the appropriate treatment was proposed. Finally, we explored the processes of consolidation of objects made of polyurethane foam. Among the promising solutions, aminoalkylalkoxysilanes (AAAS) seem to offer a "last chance" treatment to reinforce dilapidated objects.

We have almost reached the end of the POPART project. What are your initial findings ?

They are varied. In concrete terms, all information produced in the identification, exhibition and documentation of treatment of plastic works of art in museums will allow a better conservation. A lot remains to be done, but this project has given us the chance to create, for the first time, an international community of professionals from the hard sciences or social sciences as well as small and medium-sized businesses to offer innovative tools addressing this issue,

All the results of this project will be easily accessible; they will be the basis of a 300-page book published by the CTHS (Committee on historical and scientific works).

This will allow all concerned parties (conservation scientists, conservators and curators) to be informed about the state of the art and the risks and methods of conservation / restoration.

This will allow all concerned parties (conservation scientists, conservators and curators) to be informed about the state of the art and the risks and methods of conservation / restoration.

Beyond these achievements, the project marks a significant step towards understanding the issues related to these collections and helps pave the way for future work. For, though it answers many questions, it poses even more, given the relative newness of plastics and the many other materials that appear regularly and are adopted by contemporary artists. Knowledge and conservation of such heritage is still in its infancy; fortunately other teams have already taken up the challenge and new projects on synthetic polymers and art were launched in the wake of the POPART project.

POPART project partners :

Centre for Research on the Conservation of Collections, France; Istituto di Fisica Applicata "Nello Carrara", Italy; Laboratory Centre for Research and Restoration of Museums of France; Rainbow Nucléart, France; SolMateS, Netherlands; Morana RTD d.o.o., Slovenia; Getty Conservation Institute, USA; Victoria and Albert Museum, UK; Polymer Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Slovakia; The National Museum, Denmark; Centre for Sustainable Heritage, UK; Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands

Several museums have collaborated in this project, including:

The Danish National Gallery in Copenhagen (Denmark); The Museum of Modern Art and Contemporary Art in Nice (France); The Museum of Modern Art in Saint-Etienne Métropole (France); The Museum of Fashion and Textiles and the Galliera Museum in Paris (France); The Centro per l'Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci - Prato (Italy); The Serralves Museum in Porto (Portugal); The Science Museum in London (UK), etc.

This project has created new synergies between conservators and scientists who studied hundreds of objects together in the context of this research.

MORE INFORMATION