Predicting the impact of materials beyond humanitarian emergencies.

What exactly does your humanitarian design work entail ?

It should be noted, first and foremost, that it is a form of industrial design aimed at distributing mass-produced products and objects rather than brand enhancement. We are therefore called upon to intervene at the earliest stages of industrial projects. However, we are asked to work in a much more "intrusive" way than our colleagues who work exclusively with industrial partners.

It is in this regard that the specificities of humanitarian work require us to change our approach.

In what way ?

In many industrial sectors, designers are generally in contact with a single contractor, the manufacturer, represented by a few members of their engineering department who therefore have an understanding of design. This type of situation does not happen in the humanitarian sector, which is extremely fragmented. This makes it difficult to design and evolve mission-critical products, object and equipment.

In many industrial sectors, designers are generally in contact with a single contractor, the manufacturer, represented by a few members of their engineering department who therefore have an understanding of design. This type of situation does not happen in the humanitarian sector, which is extremely fragmented. This makes it difficult to design and evolve mission-critical products, object and equipment.

NGOs and international organisations might seem like the preferred type of partner for a designer in realising this type of project. Unfortunately, this isn't always true. In fact, there is no single point of contact: we have to take into account the requirements of all parties taking part in the humanitarian action, during the initial stages, such as funders and equipment suppliers. We also need to take into account the expectations and prohibitions of all those involved in the operational phase, all the way to the recipient. This can include the smuggler and the camel driver, in certain cases.

Are such requirements incompatible ?

Not necessarily, although they are sometimes poorly expressed. In reality, our partners' diversity poses much less of a problem than their ability, or lack thereof, to express specific requirements in terms of design in a set of specifications, for instance.

Not necessarily, although they are sometimes poorly expressed. In reality, our partners' diversity poses much less of a problem than their ability, or lack thereof, to express specific requirements in terms of design in a set of specifications, for instance.

This is normal, since operational players such as NGOs have a financing culture and method which is based around urgency. It has to be said that this does not encourage them to invest in medium- and long-term Research and Development projects of which funders may disapprove.

Finally, collaboration with humanitarian equipment suppliers is just as complicated. Outside of certain industry partners who have specialised in humanitarian action, most of the sector's suppliers do not have a specific approach for this market and some are even unaware that they are providing equipment to the sector.

Is it possible to innovate in these conditions ?

Let's be honest: the "tyranny" of urgency faced by operational players does not prevent them from systematically taking stock of their interventions and from conducting joint reflection on the improvement of their equipment and the design of new equipment.

Demand for humanitarian design does exist, and we are able to rely on collective expertise to meet it. Our mission, therefore, consists in formulating an answer through a three-phase project: urgently meeting a need, predicting social and environmental impacts during the transition phase, and preparing the reconstruction phase, to the extent possible.

This three-stage approach is applicable to a wide range of products for health, education, food, housing and water management, among others.

Where do humanitarian aid recipients fit in in this process ?

They obviously occupy a central place, but their contribution is not the same in each step. During a crisis, the displaced and/or homeless victims of a crisis have nothing left and are inevitably entirely dependent on humanitarian players. It is then up to the latter to define the basic requirements for the product to be designed. Our role, at this stage, is to help them not to sacrifice everything on the altar of immediate effectiveness by anticipating the way in which the recipients will use the products that have been distributed as well as their medium-term impact on the environment and on ways of life.

They obviously occupy a central place, but their contribution is not the same in each step. During a crisis, the displaced and/or homeless victims of a crisis have nothing left and are inevitably entirely dependent on humanitarian players. It is then up to the latter to define the basic requirements for the product to be designed. Our role, at this stage, is to help them not to sacrifice everything on the altar of immediate effectiveness by anticipating the way in which the recipients will use the products that have been distributed as well as their medium-term impact on the environment and on ways of life.

In short, is it a form of eco-design ?

Not at all. Eco-design, as practiced in industrialised countries, is an issue faced by rich people living in an affluent society and threatened by the negative effects of over-abundance. The concept is based on the idea of recycling, with its own dedicated infrastructure. This is not the case in humanitarian crises. More often than not, such infrastructure is lacking and, when they do exist, they have been destroyed or are largely defective.

Not at all. Eco-design, as practiced in industrialised countries, is an issue faced by rich people living in an affluent society and threatened by the negative effects of over-abundance. The concept is based on the idea of recycling, with its own dedicated infrastructure. This is not the case in humanitarian crises. More often than not, such infrastructure is lacking and, when they do exist, they have been destroyed or are largely defective.

In situations where permanent or situational shortages are rife, reuse must take precedence over recycling. Two of our recent projects illustrate this concept perfectly.

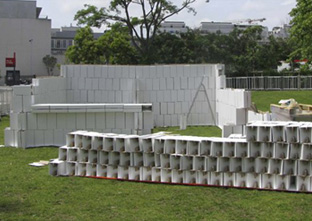

The first project led us to reconsider the packaging of the Nutriset food rations. Instead of considering the improbable notion of recycling cardboard, we designed a new form of packaging which, in addition to meeting the stringent requirements of emergency logistics, can be reused as a brick for constructing isolating walls or as bedding to protect undernourished people who are very sensitive to the cold.

For the second project, we simply offer to replace the cardboard packaging of the ICRC cookware with a plastic container which can be used sustainably by the families receiving the aid packages.

What place do plastics generally occupy in your approach ?

As shown in both examples above, their role can vary according to the context of the humanitarian action. The materials are very adaptable.

We have noted, for instance, that once emergency respondents leave the field after completing their mission, they often abandon piles of waste whose disposal falls to the persons taking over during the transitional phase.

In such conditions, I believe that the manufacturers and designers of emergency humanitarian equipment have to take responsibility for the use and introduction of plastics.

There is no prohibition on the use of plastics, and their use is sometimes necessary as with our cookware. However, the decisions must take into account, moreso than in industrialised countries, the populations' ability to take care of the end of life cycle, in the widest sense, of their packaging without harming their health and the environment.

MORE INFORMATION

www.humanitariandesignbureau.com/

Copyright : Humanitarian Design Bureau