Polymers strike a chord

The plastic touch sets the tone

The story goes that the first plastic material, celluloid, was developed to replace the ivory in billiard balls. In fact, the ivory shortage affected many other trades such as piano-making.

Throughout the 19th century, many patents were filed for the finishing on keys, whether in glass, enamel, bone, horn, mother-of-pearl, pearl or porcelain…The advent of synthetic materials was a godsend!

In the 20s, celluloid was replaced by galathite, a thermosetting polymer made from milk casein. After World War II, manufacturers started using various polyester resins, reconstituted ivory for the white keys and phenolic compounds as a substitute for the very costly ebony used on the black keys.

These materials were dethroned in the 60s by acrylic resins used for covering the traditional wooden keys of classical pianos or for manufacturing the 100% plastic keys of many electronic keyboards: organs, synthesizers and digital pianos.

Methacrylates enter stage left

After over a century of traditional woodworking, the Art Deco movement finally pushed piano makers towards new materials. In 1929, Pleyel started the ball rolling with a glass grand piano with copper finishing. In 1936, Blüthner created a small-size duralumin model for Zeppellin, followed in 1937 by Rippen, who made an aluminium piano that was mass produced by 1948, shortly before the first appearance of methacrylates.

After over a century of traditional woodworking, the Art Deco movement finally pushed piano makers towards new materials. In 1929, Pleyel started the ball rolling with a glass grand piano with copper finishing. In 1936, Blüthner created a small-size duralumin model for Zeppellin, followed in 1937 by Rippen, who made an aluminium piano that was mass produced by 1948, shortly before the first appearance of methacrylates.

Thanks to the Glas Piano, presented in 1951, Schimmel had the monopoly on transparent pianos for long until the launch of Japanese manufacturer Kawai's Crystal models in the 1980s.

Recently, some manufacturers have taken to specialising in the manufacture of such pianos destined to a wealthy, even eccentric, clientele. In the Netherlands Crystal Music Company only makes transparent Vitroflex pianos. French manufacturer Gary Pons marries aluminium and Altuglas in his Plexart range.

Recently, some manufacturers have taken to specialising in the manufacture of such pianos destined to a wealthy, even eccentric, clientele. In the Netherlands Crystal Music Company only makes transparent Vitroflex pianos. French manufacturer Gary Pons marries aluminium and Altuglas in his Plexart range.

Despite their elegant design, a far cry from Liberace's kitsch Baldwin recently exhumed for Soderbergh's biopic, these pianos are finding it hard to carve their niche on the top classical stages.

Plastic pianos play on

The first plastic mechanism installed on an affordable piano at the end of the 40s was not successful and its attractive price did not help. This innovation not only intended to serve as a guarantee of quality construction, it provided the instrument with greater stability with regard to variations in temperature and humidity. This also explains the sudden interest of famous manufacturers such as Mason & Hamlin in the United States and Pleyel in France. Unfortunately, the decision to use poorly formulated PVCs proved problematic. It showed signs of premature ageing, a lack of elasticity and increased fragility. Its defects almost cost polymers their place in the future of pianos, and almost cost the prestigious brands their reputations.

Dutch manufacturer Rippen was more successful in the 60s thanks to their Lindner, a small upright piano with an aluminium frame and a mechanism using new plastics, including nylon.

At the start, Japanese manufacturer Kawai was the one to make plastics indispensable by using ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene) in its top-end models. Better yet, it made their innovation, the ABS and carbon fibre Millennium mechanism, a very popular offering.

At the start, Japanese manufacturer Kawai was the one to make plastics indispensable by using ABS (acrylonitrile butadiene styrene) in its top-end models. Better yet, it made their innovation, the ABS and carbon fibre Millennium mechanism, a very popular offering.

It is only during the first years of the new millennium that new materials replaced the maple and spruce used in soundboards.

Steingraeber & Söhne achieved this in 2007 with their Phoenix models which combine wood and carbon fibre. In 2012, British manufacturer Hurstwood Farm Piano Studio took the next step, at the Cremona show, by unveiling a prototype of a grand piano with a soundboard and frame made entirely from composite materials.

Millions of ukuleles and a guitar !

Hector Sommaruga, inventor of the Grafton sax, was not the only one to pioneer the use of plastics in music. His fellow countryman Mario Maccaferri successfully followed the same route overseas.

Hector Sommaruga, inventor of the Grafton sax, was not the only one to pioneer the use of plastics in music. His fellow countryman Mario Maccaferri successfully followed the same route overseas.

After having made his fortune in the manufacture of plastic objects, from clothes pegs to saxophone reeds, this astute businessman and erstwhile guitarist returned to his roots in violin making.

In 1950, he launched the Islander, an ukulele designed for singer Arthur Godfrey, manufactured from Styron, a polystyrene made by Dow Chemical. Bingo! Starting with 30 units in January, production increased to 1,188 in February and 18,900 in March. It stabilised in May at around 2,500 units per day as competitors grappled for their part of the market.

Maccaferri paid them no heed and created variants of the Islander, in gaudy colours, luxury models, baritone models or limited-edition models named after celebrities of the time, and even a guitar, put on sale in 1953, albeit less successfully.

In total, he sold over nine million instruments between 1950 and 1969, when production was halted. Unfortunately, he never launched his plastic violin.

Maccaferri had invested 350,000 dollars in the instrument while still at the prototype stage, and which was unveiled to the public at Carnegie Hall in 1990. The press welcomed it with no small amount of irony but without being contemptuous of the instrument!

Rock musicians go against the grain !

The advent of electric guitars and basses, in the wake of rock and pop, didn't spark a craze for synthetic materials. And with good reason. The solid-body electric guitar doesn't have a resonance chamber - it makes a sound but doesn't reverberate! There was no talk of abandoning wood, however, even for the solid body guitars. Most of the current generation of guitars adhere to this tradition imposed by legendary models, manufactured from precious woods, such as the Fender Stratocaster and the Gibson Les Paul.

The advent of electric guitars and basses, in the wake of rock and pop, didn't spark a craze for synthetic materials. And with good reason. The solid-body electric guitar doesn't have a resonance chamber - it makes a sound but doesn't reverberate! There was no talk of abandoning wood, however, even for the solid body guitars. Most of the current generation of guitars adhere to this tradition imposed by legendary models, manufactured from precious woods, such as the Fender Stratocaster and the Gibson Les Paul.

Even for finishes, tradition reigns supreme in top-end models where the use of nitrocellulose lacquers, developed in the 20s for the bodies of American cars, are still in use. Polyurethane, polyester and acrylic varnishes are used for regular guitars while all-plastic guitars are for amateur musicians!

Acoustic guitars bet on composites

Starting with the Islander, grafting polymers into instrument-making found its niche with acoustic guitars. This however, was not a matter of manufacturing affordable instruments out of pieces of molded resin. The aim was to replace the traditional woods with easy-to-shape synthetic materials which were at least as effective, if not more so, in terms of lightness and acoustics. This approach was only possible for top-end instruments.

Starting with the Islander, grafting polymers into instrument-making found its niche with acoustic guitars. This however, was not a matter of manufacturing affordable instruments out of pieces of molded resin. The aim was to replace the traditional woods with easy-to-shape synthetic materials which were at least as effective, if not more so, in terms of lightness and acoustics. This approach was only possible for top-end instruments.

All instrument makers who have chosen this direction have opted for the composite solution, based on carbon fibre-reinforced polymer resin. It has already converted many Americans through the Blackbird, Ovation and Rainsong folk guitars. In Europe, only the Ireland-based Emerald Guitars has been flying the banner of composites for the last decade. Since then, a small circle of instrument makers and classical guitarists have been experimenting with composite manufacture.

Transparent playing on the Cello 2.0

Violinists are less old-fashioned than rock guitarists and don't mind playing instrument with futuristic lines, whether made from composite resins or not. More than a simple passion for design, they show a manifest interest for ergonomics. Unfortunately, despite the absence of a resonance chamber, electric violins suffer from a weight problem; they tend to weigh in at 700 grams as compared to the average of 500 grams for a well-made traditional violin, and 370 grams for a Stradivarius with its strings. The weight difference often weighs heavily under the chin rest. Using polymer resins is often the only way to recreate a shape and size which are adapted to the musician's posture.

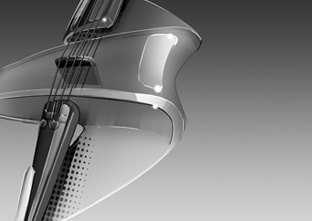

Bayer Material Science took this rationale to its logical conclusion in creating the Cello 2.0. This futuristic cello combines an aliphatic polyurethane body with a magnificent transparent polyurethane scroll. It is a compromise between elegance, lightness and stability, although the construction aims to achieve more than simple ergonomics. The ambition remains to make Cello 2.0 an interactive musical instrument.

Bayer Material Science took this rationale to its logical conclusion in creating the Cello 2.0. This futuristic cello combines an aliphatic polyurethane body with a magnificent transparent polyurethane scroll. It is a compromise between elegance, lightness and stability, although the construction aims to achieve more than simple ergonomics. The ambition remains to make Cello 2.0 an interactive musical instrument.

The LEDs and mini video projectors integrated into the instrument's body display graphical effects on its transparent face. These are signals which can highlight both a musician's virtuosity and his clumsiness.

Acoustic violins take sail

Instrument makers' fascination with innovative materials has also taken hold in the world of classical violinists, who are often considered to be more conservative.

Instrument makers' fascination with innovative materials has also taken hold in the world of classical violinists, who are often considered to be more conservative.

In 1989, Luis Leguía, a cellist in Boston's Symphony Orchestra and sailing enthusiast, stumbled upon the idea of creating a cello from carbon fibre. After having constructed three cellos, he called on naval architect Steve Clark, head of the renowned Vanguard Sailboats naval yard with the aim of launching a full range of instruments.

From the violin to the double bass, the whole range of string instruments, in composite versions, is available under the Luis & Clark brand.

In Europe, German company Mezzo-Forte, originally bow manufacturers, is the only one to have taken on the challenge. It launched a range of carbon fibre violins in 2011, and an alto and a cello in 2012.

Corrus takes a bow with synthetic fibres

Although devoted to manufacturing techniques that have remained unchanged for over 250 years, bow makers have no qualms about trying various materials. Carbon fibre bows are more durable than their Pernambuco cousins and can be found in many catalogues, and not just at the entry-level where the price and durability of these composite bows seduce students and beginners.

Top-end models are increasingly sought-after by professional musicians looking for a reliable alternative to their wooden bows which are highly sensitive to variations in temperature and humidity.

The sticks of carbon fibre bows are more reliable, but the ribbons are particularly delicate. So delicate, actually, that professional musicians have to replace them once every three months on an average. They need to be replaced very often as the ribbons, sourced from Mongolia, tend to degrade very rapidly.

The sticks of carbon fibre bows are more reliable, but the ribbons are particularly delicate. So delicate, actually, that professional musicians have to replace them once every three months on an average. They need to be replaced very often as the ribbons, sourced from Mongolia, tend to degrade very rapidly.

Gilles Colliard, a violinist at the Toulouse Chamber Orchestra, has come up with a solution. With the help of the French Institute of Textiles and Clothing (IFDH) and his colleagues, he developed a new ribbon made from a synthetic fibre christened "Coruss".

The orchestra tested the new ribbons made from composite materials over the course of several months and found them to be perfectly satisfactory. They have a uniform diameter and are hydrophobic, meaning that they do not stretch in a humid environment. As a result, they last twice as long.

Mylar shakes to the rhythm

Drum shells are open to new experiences and can accommodate a wide variety of materials: metals such as aluminium, synthetic materials such as acrylic, fibreglass and carbon fibre and, preferably, plywood panels.

Drum shells are open to new experiences and can accommodate a wide variety of materials: metals such as aluminium, synthetic materials such as acrylic, fibreglass and carbon fibre and, preferably, plywood panels.

In terms of vibrations, however, synthetic skins have conquered most percussion instruments, from drum kits to symphony orchestras.

The fact that synthetic skins are currently championed by two famous brands of percussion instruments, Evans and Remo, both founded in the 50s by drummers of the same names, stands as a testament to the importance of this particular invention.

The only facts on which the two alleged pioneers agree are the problem and the solution. Both were looking for a material which was stronger than calf skin and less sensitive to variations in temperature and humidity. As it happens, each of them independently came up with the idea of stretching a Mylar polyester film over a drum shell! Although it isn't possible to determine who first had the idea, one thing is certain: from 1957, the main manufacturers of skins adopted polyester membranes, so improving the quality and diversity of their products.

They currently offer single skins, made with a single film, in varying degrees of thickness with maximum resonance and clear attack, as well as double skins offering a full harmonic sound although they are less reactive. Finishes are equally important. They can be opaque, transparent or printed, according to the desired look; the skins are also sanded in order to obtain a coated effect under the brushes.